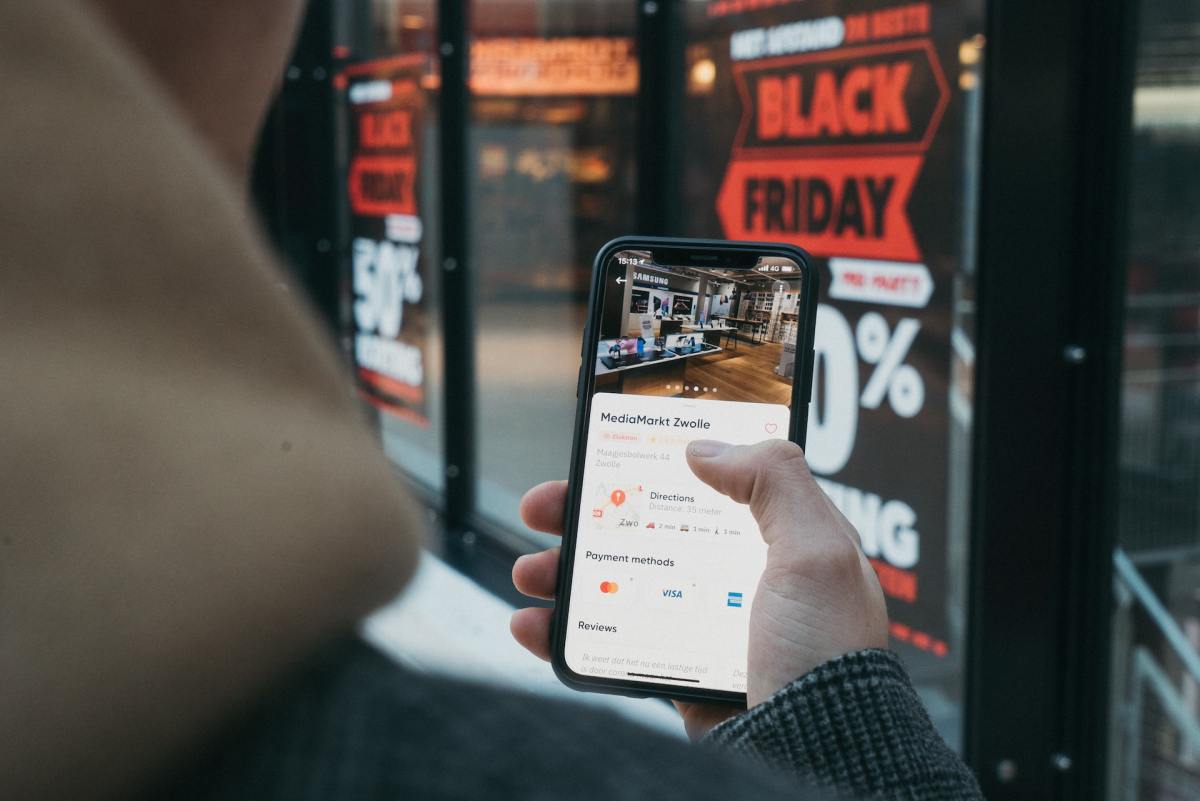

Two from the busiest shopping online times of the entire year are upon us. In the center of a cost-of-living crisis and recession, retailers will be desperately hoping that shoppers make the most of discounts on Black Friday and Cyber Monday to bump up annual sales figures.

While this could boost a sector which has yet to completely get over the COVID pandemic, there is a major downside. The greater that shoppers order online, the bigger the trouble with returned goods.

Almost 60 million people shop online in the UK – in other words the vast majority. But many shoppers buy more than they intend to keep. They order multiple sizes and colours to obtain the perfect item, safe knowing there is a convenient and “free” return option to get rid of the rest.

The returns nightmare

This has become so standard that there's a name for it – “wardrobing”. Around 66% of individuals in the united kingdom think about the returns policy before choosing online, and abandon orders once the policy isn't obvious. Ten percent shoppers even admit to buying clothes solely for the purpose of taking a photo for social media.

More than 1 / 2 of all clothes purchased online are returned. Put another way, each British shopper returns typically one item monthly.

But if individuals have become accustomed to treating their bedrooms and living rooms as the new in-store changing room, it is not only clothes that cause an online returns problem. For instance, 42% of electrical goods ordered online get returned, mostly because they arrive damaged or faulty.

Returned goods are a lot more complex to process than other stock because they tend to arrive as single items that need inspecting individually to see why these were returned. They need sorting and perhaps repairing or cleaning before being returned to stock, which for many retailers is in another location.

The associated cost is significantly higher than shipping out new products. Based on one US expert, every dollar in returned merchandise costs a retailer between 15 and 30 cents.

Returns were estimated to be costing retailers about lb20 billion a year in 2023, roughly half those of shop-bought products. Since then, it'll have increased considerably – particularly during COVID as online sales went through the roof.

Every time you progress an item there's also environmental costs associated with the journey. Based on one recent study, the carbon emissions from returning a product are about a third greater than shipping it out to begin with.

What can be done

It is tempting to consider we need rules to curb all this over-buying and returning. But that would be tough to police as well as potentially disastrous for online stores.

In any case, the sector is developing its own solutions: a quarter of leading UK brands now charge customers for returns, including fast-fashion players like Zara and Boohoo. They're not going to be doing this lightly: the Royal Mail estimates 52% of customers would be unlikely to utilize a particular online retailer if they had to purchase the returns.

We both still see reports online claiming that substantial amounts of returned clothes end up in landfill, but this is not what we should hear from our discussions with leading retailers. Over 95% of returned clothing could be reprocessed making available for resale like a cool product – subject to cleaning and sewing repairs and retailers having access to ozone cleaning facilities to remove perfume/aftershave smells, that is actually a major one issue.

Our understanding is the fact that many retailers are approaching that sort of turnaround figure. ASOS reportedly resells over 97% of their returns, for example.

Challenges with bulky goods

Unfortunately it is extremely different with bulkier goods like furniture or kitchen appliances. These often require additional packaging, two-person collection plus much more besides.

Take memory foam mattresses. A consumer returning one won't be able to squeeze out all of the air and put it back in the modest-sized delivery box. The return will therefore function as the size a mattress, and also you can't have that many on the truck.

Mattresses have also been slept on so there are hygiene considerations. The coverage must be washed or discarded, based on its condition. The mattress needs to be inspected for damage like scuff marks, then cleaned and sanitised prior to being reboxed to be removed as reconditioned.

There are comparable challenges across the board with bulkier products. To give another example, electrical merchandise is expensive to repair by law need to be tested before they may be resold.

Faced with such issues, retailers frequently go ahead and take easy way out. They let returns languish in distributors' warehouses before eventually sending them to landfill.

We have seen this first hand in our research, dealing with four major retail brands which use returns specialist Prolog. One beauty retailer insists their returned electrical products in beauty kits be destroyed to protect their brand, resulting in many being sent to landfill.

We were able to demonstrate that these items could be processed more sustainably by harvesting the unused components for new kits, retained by Prolog Fulfilment for supplying missing components to other customers, or salvaged for warranty replacements.

These sorts of choices are available with a bit of investigation. Sometimes value engineering can also be possible, where engineers repair returned products and provide feedback to manufacturers about common reasons for returns.

Carbon footprints may also be reduced. For instance, the delivery company could contain the returns rather than sending them back to the retailer's distribution centre. Will still be commonplace for retailers to process returns in a different location where they ship out services, so companies need to look only at that too.

These failures are generally unacceptable from the sustainability point of view but additionally a major missed selling opportunity. Many returns might be refurbished with no work and sold as “A-” grade in a small discount.

When products can't be resold, other available choices include resizing, donating to charity or working with specialist recycling companies to dismantle and recycle small components to prevent any material likely to landfill.

As everyone gears up for that Black Friday weekend after which Christmas, it's the perfect time of these retailers to complete better. Consumers also need to be aware of this problem and apply more pressure.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation. Browse the original article.