Balking at Balkan babies

The demography of south-eastern Europe threatens its about prosperity

SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE is within a Catch-22. The region's many problems prompt young, talented people to leave in droves. However it won't catch up with the remainder of Europe without young, talented people to generate prosperity. Across the Balkans, populations are shrinking and ageing, and unless that changes even more will leave.

Measuring demography within the Balkans is tough: aside from those for births and deaths, data are difficult to find. A lorrydriver who leaves Belgrade to consider a job in Germany does not have to inform the Serbian authorities. Because of the region's complicated history, countless its citizens can get passports from neighbouring “mother countries”. These are especially attractive if the mother country belongs to the EU, since EU citizenship includes the right to work any place in the union. A fifth of Croatian passport-holders working abroad are probably from Bosnia, and just about all Moldovans employed in free airline have Romanian documents. All this makes it hard to tell who is where.

Yet the data that are available paint the answers. The population of every Balkan country is shrinking because of emigration and low fertility. In the past, populations grew back after waves of emigration, since many women had six children. Now few have more than one. Serbia might have more pensioners than working-age people by the coming year.

In rapid run governments don't mind emigration since it lowers unemployment and increases remittances from abroad. However in the long term, says Vladimir Nikitovic, a Serbian demographer, it is “catastrophic”. About 50,000 people leave Serbia every year. Of those who return, around 10,000 are pensioners who have spent their working resides in the West. Their kids will not follow it well.

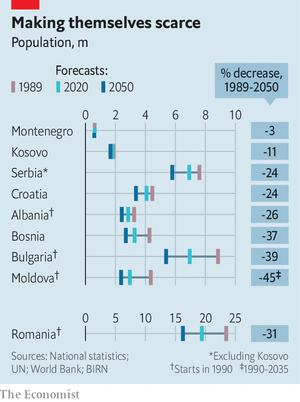

On current projections Bulgaria will have 39% fewer people by 2050 than it did in 1990 (see chart). The location has a few of the world's lowest fertility rates. Bosnian women have an average of 1.3 children and Croatians 1.4. Kosovo, with a median age of 29, has the region's youngest population, but its fertility rate of 2.0 (just below the replacement rate) has been falling for a long time too. Elsewhere, rates are similar to the ones from western European countries. But because the Balkans host hardly any taxpaying immigrants, money for pensioners is scarce.

The results of population shrinkage are stark. In the height of the summer holidays Rasnov, quite a town in Romania's Transylvanian hills which had a bustling marketplace, is eerily empty, with barely a café open. An era ago its ethnic Saxon population, which traced its roots to the Middle Ages, left for Germany. Its ethnic Romanians seek work elsewhere. They send money the place to find ageing parents, but few come back except to retire. Why work in a café in Rasnov when you can perform the same for far more money abroad?

A some of the region's cities have become. Cluj, another town in Transylvania, is booming. Albania's capital, Tirana, can also be drawing people in. Its mayor, Erion Veliaj, says it faces an influx of 25,000 people every year. But those are exceptions.

This mixture of rapid emigration, low fertility and sparse immigration creates the worst imaginable result, says Kresimir Ivanda, a Croatian demographer. Greece, Italy and Spain have low birth rates, but attract plenty of immigrants. In Poland, a lot more than 1m Ukrainians have filled gaps in the labour market left by emigration.

Mr Nikitovic helped a national commission on solving Serbia's demographic crisis, but the government, he states, did not act on enough of its suggestions to make much difference. As in many Balkan countries, the issues are legion. Women are discouraged from having more children through the lack of protection against being fired when they conceive. Cheap air travel makes seeking work abroad easy (or did before covid-19 struck). In normal times, Croatian carers in great britan or Romanians the german language slaughterhouses can commute to short-term jobs. This worsens labour shortages at home, which in turn pushes up wages. Ivan Vejvoda, from the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, thinks meeting western Europe's needs without draining the Balkan countries of the people requires concerted action through the EU and also the states from the region.

Of course, for citizens of Balkan countries, earning higher wages abroad is really a boon. Remus Gabriel Anghel, a Romanian demographer, says the migration experiences of the past 15 years have also been an electric motor of social change. Before, people just wanted to make payments; now those who have lived in western Europe demand better schools, hospitals and services. This, Mr Anghel says, is something the federal government “does not really understand”. ■

From The Economist, published under licence. The original article in English can be found on www.economist.com