MADRID – As two weeks of UN climate talks come from Madrid on Monday, one contentious issue will occupy diplomats more than every other.

Under the Paris Agreement (the appropriate section is Article 6), countries decided to set up a new global carbon market system to assist countries decarbonise their economies at less expensive.

Countries have tried and failed to agree the guidelines governing this mechanism. It is the last portion of the Paris accord rulebook which remains unresolved and contains the potential to create or break efforts to curb emissions.

How are markets from the Paris Agreement?

A majority of national climate plans include the use of carbon markets to attain cheaper emissions reductions. Most commonly this means governments and the private sector can trade emissions reductions.

But some governments could also look to buy carbon credits to build up green projects made to cut emissions internationally. Others which have cut emissions beyond their target could sell their overachievement to countries struggling to meet their set goals.

Not all countries uses these credits. For the time being, Finland and also the UK, for example, have said they will not rely on them to achieve their net zero targets. Norway and Canada, however, will.

The Paris Agreement sought to establish a typical algorithm to manipulate these transactions and ensure they result in global emissions cuts.

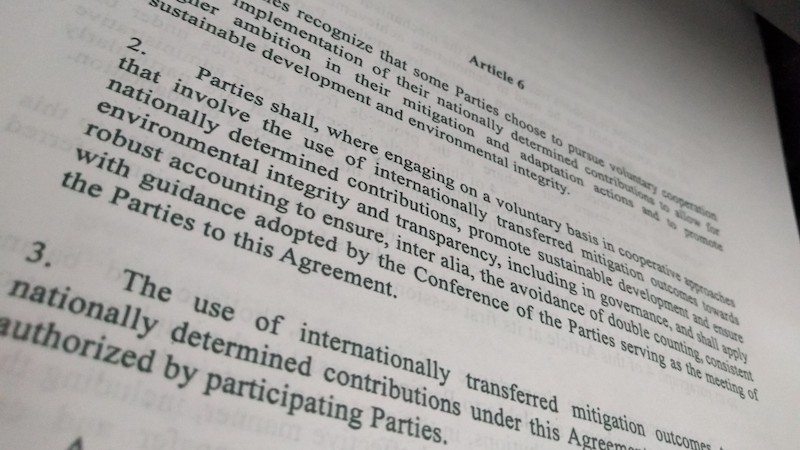

What is Article 6?

The framework defined by Article 6 from the Paris Agreement is divided into three sections.

Article 6.2 allows countries to strike bilateral and voluntary agreements to trade carbon units.

Article 6.4 results in a centralised governance system for countries and also the private sector to trade emissions reduction all over the world. This technique known as the Sustainable Development Mechanism (SDM) is a result of replace the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), established under the Kyoto Protocol.

Finally, Article 6.8 develops a framework for cooperation between countries to reduce emissions outside market mechanisms, for example aid.

Under the Paris Agreement, a share of arises from the markets must be deployed to assist developing countries adjust to climate impacts. Whether this applies towards the centralised SDM market only in order to all trading, including from bilateral agreements has not yet been agreed.

What reaches stake within the negotiations?

While the text of the Paris Agreement isn't up for discussion, Article 6 is just two pages long and does not describe how scalping strategies will work and just what rules will ensure they lead to real emissions cuts.

The issue is paramount to the integrity of the Paris Agreement and negotiators have warned that weak rules could undermine the entire accord as well as result in an increase in emissions.

“How these rules are decided is actually going to make or break the ambition from the Paris agreement,” said World Resources Institute senior associate Kelly Levin, adding that weak rules “can lead to a rise of worldwide emissions”.

At the latest climate talks in Bonn in June, Costa Rican negotiator Felipe de Leon Denegri told Climate Home News: “Article 6, unlike just about anything else within the [UN climate negotiations], can do actual active harm.” He added there was a “quite substantial” chance of introducing loopholes that undermine the ambition of the deal.

“The risk is that carbon markets are used like a trick to meet emissions reduction targets on paper. They can be used as an excuse not to do very much in practice,” warned Gilles Dufrasne, policy officer at Carbon Market Watch.

However, a strong algorithm could help bolster ambition.

In talks which have now lasted several years, negotiators happen to be unable to overcome some major sticking points.

Sticking point 1: CDM credits

Brazil, India and china wish to trade their surplus of old credits from the previous CDM regime around the new market set-up under the Paris Agreement. However the CDM has been mired in allegations of human rights abuses and corruption with a majority of projects found unlikely they are driving emissions cuts.

Experts have warned this risked flooding the market with credits of no value and undermine global efforts to curb emissions. This is one of the thorniest issues within the negotiations, which require consensus. In 2023, Brazil forced this of the Paris rules to become extended for an additional year even while the rest of the Paris rulebook was agreed.

Marina Grossi, a former negotiator and president of Brazil-based CEBDS, a non-profit organisation promoting sustainable development for businesses, told CHN the Brazilian government wanted flexibility in the manner the guidelines are implemented.

“The government isn't attempting to be an obstacle to Article 6” but instead act in way that “it can take advantage of this new market,” she said. Grossi suggested a period of transition during which old credits could be traded on the new market could bring Brazil on side.

Sticking point 2: The corresponding adjustment (or avoiding double counting)

Brazil has also pushed back against rules to avoid double counting emissions reductions. Most countries argue emissions cuts can't be claimed by both country that built them into and also the country that bought the offsetting credit.

To ensure a reputable system, countries who sell credits to other countries will need to improve their own reported emissions through the same amount. But the rules remain under discussion, with Brazil arguing this so-called “corresponding adjustment” is not needed initially.

If emissions reductions are reported twice by two different countries, “there isn't much point having targets in the first place,” warned Dufrasne.

Sticking point 3: Overall mitigation

Another key concern is to guarantee the new market doesn't allow transfers of emissions reduction across borders without generating additional cuts.

Countries have to agree on a method to ensure “overall mitigation” of the market. But there is disagreement over which from the three kinds of market (6.2, 6.4 and 6.8) is going to be governed by this principle. The Paris Agreement text only Article 6.4 includes this goal. More progressive negotiating blocs reason that all markets have to stick to this principle or the system will be distorted.

How this is achieved can also be up for debate, with some suggesting a systematic ‘cancellation’ of credits to the benefit of the atmosphere.

What stage possess the negotiations reached?

A deal was not far from being carried out in Katowice, Poland last December. But since then your conjecture has widened, rather than shrunk, based on research into the quantity of square brackets (points of disagreement) in the negotiating text by Carbon Brief. In Katowice, all of those other Paris rulebook was being negotiated and countries were pushing hard to agree everything. Now that Article 6 has been siloed, that pressure has dissipated.

The latest texts governing Article 6.2, Article 6.4 and Article 6.8 are full of 672 square brackets, all of which need to be resolved for that Madrid talks to close this problem.

What happens if the talks fail?

Negotiations on carbon markets are technical but this doesn’t prevent highly politicised positions. Discussions are anticipated to be tough.

If an agreement can't be found, the problem will be kicked further in the future to Cop26 in December the coming year.

Resolving Article 6 is the major agenda item for Cop25. But failure is really a perception the UN, Cop hosts, national governments and parts of civil society traditionally try to avoid. If things drag on to 2023, expect a fudge to leave Madrid. This might are available in the type of a ‘partial resolution’, where some things of disagreement are declared agreed with a narrower discussion tabled for 2023.